On Kauai, it takes a village to ensure the protection of a beloved seabird.

Last year, while on a bird-watching tour of Kauai, the lushest and least developed of the four main Hawaiian islands, we went with a guide to a suburban-style development where a wide-eyed Laysan albatross chick was sitting by herself in a nest of lawn clippings and leaves on the grass island of a cul-de-sac. When a hefty man approached with a large dog straining at its leash, I thought, “Uh-oh, we better tell him to keep his dog away from this chick.”

The hatchlings can’t fly until they fledge at almost six months old, leaving them defenseless. And the Laysan albatross is unafraid of predators, having evolved before humans introduced dogs, cats, and pigs to Hawaii.

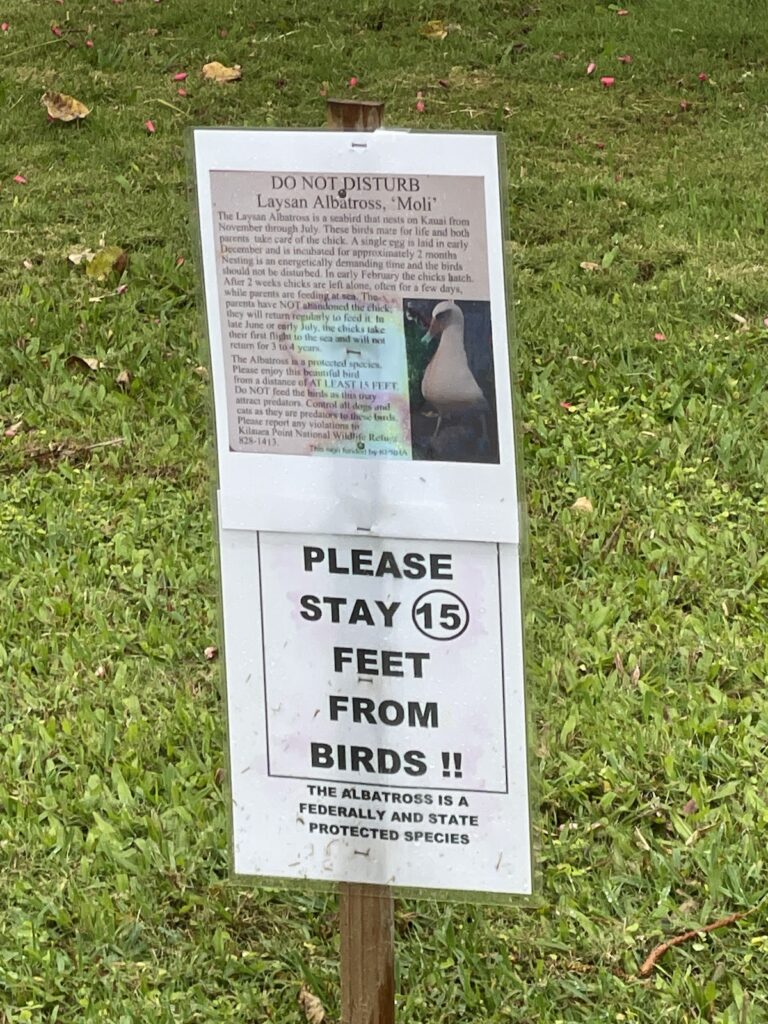

But I needn’t have worried. The dog-owner, it turned out, was one of several neighbors engaged in protecting the chicks hatched on their lawns — erecting traffic cone barriers to keep chicks from wandering into the street and posting signs asking visitors to keep their distance.

There are numerous such citizen efforts on the island to protect the magnificent Laysan albatross, a giant seabird that is listed as “near threatened,” thanks in large part to Hob Osterlund, founder of the Kauai Albatross Network — a group of organizations and volunteers dedicated to protecting the Laysan albatross. Osterlund estimates that during the birds’ November‒June breeding season, hundreds of Kauai residents are involved in some way to protect the chicks.

Each Laysan albatross chooses a mate for life, laying one egg a year, with both parents spending equal time incubating the egg and feeding the chick — flying hundreds of miles seeking food before their baby fledges.

The fledglings then spend roughly three years roaming the ocean for thousands of miles, never touching down on land, before returning to breeding grounds to search for a mate. Breeding adults generally return to the same spot where they were hatched to lay their eggs, rejoining the mates they have chosen, typically after both parents have spent months apart foraging for food at sea.

Scientists say Kauai could be the “Noah’s Ark” for the albatross — Midway, the low-lying island where the majority of the birds breed, is expected to be submerged under rising seas in coming decades due to climate change. But Kauai isn’t without its own threats. In recent years, predators — mainly cats and feral pigs — have decimated the island’s breeding colonies.

Just last year, cats killed newly hatched chicks in half of the nests at the Na Aina Kai Botanical Gardens, scooping them out from underneath their parents. Angela Serota, a volunteer there who monitors the chicks, says she and fellow volunteers were “shell-shocked” by the loss. The garden responded by placing chicken-wire over the remaining 12 nests at night. All but one chick (who died of cold exposure) survived. This year, staff at the garden are trying a new tactic to scare away cats — motion detectors that emit an ultrasonic scream.

The experience of caring for the chicks is “magical,” says Serota, a retired nurse. It is possible to walk right up to the adult birds and chicks, who usually act unperturbed — an experience Serota told me she had previously had only in the Galapagos. “If you sit there quietly, they will walk up to you, walk over your feet, and sometimes they look at you like, ‘Hmm, I don’t think you’re a bird.’ You feel like you’re in this very special magical place,” she says. What’s more, she adds, “they’re incredibly affectionate toward each other.” She loves watching the young adult single birds do the courtship dance typical of Laysans: “It’s kind of a hoot to watch them prance and preen and dance and make all their sounds.”

“If you ever doubt that birds can love, watch them reunite,” Osterlund says. “He trots to her; she trots to him. They dance, they preen, whinny and moo. … What other species does that except maybe humans?”

An added benefit to protecting the albatross is that the relationship between seabird and island is mutually beneficial. Recent research reveals that the birds’ guano — the nutrient-rich poop they excrete — helps imperiled coral reefs grow faster and stay healthy near islands with large nesting colonies. And seabirds play a huge role in the transfer of nutrients from the marine environment to the terrestrial environment, fertilizing Kauai’s lush vegetation, says Grant Sizemore, Director of Invasive Species Programs at the American Bird Conservancy.

Future Challenges and Solutions

In December, wild pigs attacked nests and ate close to half the eggs hatched at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge on Kauai’s north shore, Osterlund reports. In all, since the birds returned to breed last November, some 75 nests have been attacked by pigs on the island, leaving albatross parents dead and dismembered in 10 of those nests, she says. Considering that the season started with only 326 albatross nests on Kauai, Osterlund says, that’s a “tragic” loss for the population, especially since it takes about nine years for the long-lived birds (the oldest known is 71) to become competent parents.

A predator-proof fence under construction around the refuge should protect the nests from pigs in time for the next breeding season, scientists hope.

But outside the refuge, Kauai’s estimated 20–25 thousand feral cats remain a major threat, wildlife advocates say. While some county parks have large cat colonies that are fed regularly by cat lovers, a new county ordinance went into effect Jan. 1st that outlaws feeding stray cats or abandoning them on county property.

The county of Kauai was obligated to pass this law under a federal plan requiring it to protect endangered seabirds from predators. “We are the last bastion for a lot of these birds,” says Hawaii State Rep. Luke A. Evslin, a former Kauai County Council member. “We have responsibilities to do what we can to ensure that these species, which have always lived on Kauai, can continue to live on Kauai.”

Laysan albatross face other environmental threats, including getting hooked on long-line fishing gear and ingesting plastic that looks like food. Andre Raine, an ornithologist at Archipelago Research and Conservation in Kauai, has found clumps regurgitated by albatrosses containing toothbrushes, lighters, toys, and pieces of plastic sharp enough to lacerate the inside of the bird’s stomach. To feed her offspring, the mother will regurgitate into the chick, “which then starves to death because it’s full of plastic, not food,” he says.

Those challenges — along with climate change — require global solutions, Raine acknowledges. But he expresses cautious optimism for the future of the Laysan albatross on Kauai. “If we can create refuges where these birds can breed without threat of predators, then we can have lots of birds,” Raine says.

As for the role of citizens, “people do just get sucked in by Hob’s infectious enthusiasm for protection of this species,” Raine says. “That’s definitely a great way of dealing with conservation of the species here — having community involvement and enthusiasm.”

Great article. Brought back memories of living and working on Kauai for many years. While there my wife and I would visit Kilauea Point , the Waimea Canyon and many other more local, unknown spots. Our motivation was to witness the Laysan Albatross and other majestic seabirds. I had the privilege of assisting the rescue of several Newell’s Sherwaters. It is common for them to be confused by lights and to fall to the ground at nighttime. Residents are advised to report a downed bird for rescue. The “locals” of Kauai are committed to helping the seabird populations. Unfortunately the feral cat population is out of control.